By Jeré Longman

Northern Italy was chosen Monday as the site of the 2026 Winter Olympics, with hosting to be shared by Milan, the economic and fashion capital, and the ski resort of Cortina d’Ampezzo as the International Olympic Committee desperately tries to curb waning interest, spiraling costs and white-elephant competition venues associated with the Games.

The Italian bid was chosen over the only other candidate, a dual bid between Stockholm and the ski resort of Are, Sweden, in a vote of 47-34 by I.O.C. delegates. Northern Italy had been expected to win, given that there was much broader public support there and a greater willingness by government officials to offer financial guarantees.

While both bids offered countries where winter sports thrive and where there is experience hosting major events — Cortina hosted the 1956 Winter Olympics — the candidacies struggled at times to become convincing choices. And in the second bidding process in a row, the Winter Games ended up with only two finalists after five other potential candidates withdrew or were deemed insufficiently prepared.

With fewer cities willing to bankroll the billions needed to operate the Winter Games, the 2026 finalists reflected the I.O.C.’s effort at reform by allowing Olympic hosting to be shared by cities, regions and even countries.

The Swedish bid, for instance, planned to hold the bobsled, luge and skeleton events across the Baltic Sea in Sigulda, Latvia, where a refrigerated track already exists. But Stockholm, the Swedish capital, never seemed fully committed, even though the operation of the Games was to use no public money beyond security and the maintenance of existing infrastructure and sports venues.

Stockholm had dropped out of the bidding for the 2022 Winter Games for financial reasons — those Olympics were awarded to Beijing — and only slightly more than half of Sweden’s population had supported the 2026 bid. Stockholm officials had declined to sign the official I.O.C. hosting contract, leaving it to Are, its co-host, if the bid was successful.

It seemed, too, for a time that an Italian bid might not materialize. Nine months ago, a proposed bid among Milan, Cortina and Turin, which hosted the 2006 Winter Olympics, fell apart in a political squabble among the cities’ mayors. Italy’s sports minister declared the bid dead. It was an embarrassing moment for Italy; Rome had dropped out of bidding for the 2020 and 2024 Summer Games because of financial concerns and political opposition.

But the Italian bid for the 2026 Winter Games was recast, and it prevailed on Monday in a vote by I.O.C. delegates in Lausanne, Switzerland, where the Olympic committee is based. The I.O.C.’s polling showed that more than 80 percent of Italians supported the candidacy.

The initial operating budget is projected at $1.7 billion, but those costs always rise, often significantly. The I.O.C. has pledged to contribute $925 million to the organizers from television rights, corporate sponsorships, ticket sales and merchandising.

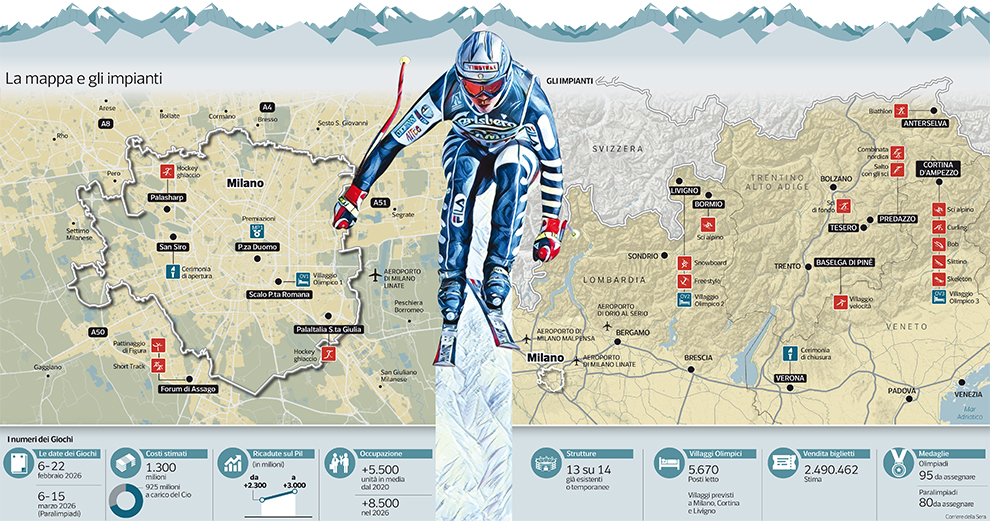

Italy has proposed to spread the 2026 Games among several cities between Milan and Cortina, which are about 250 miles apart. The opening ceremony will be held at Milan’s San Siro soccer stadium, which hosted the 1990 soccer World Cup, and the closing ceremony is scheduled to take place in an amphitheater in Verona.

The costs of hosting the Winter Games drew a jaw-dropping reaction when Russia spent $51 billion to construct and operate the 2014 Olympics in the Black Sea resort of Sochi.

The 2022 Games were awarded to Beijing almost by default as a number of potential host cities withdrew. The only other remaining bidder was Almaty, Kazakhstan, located in a former Soviet republic that gained its independence in 1991, built only mixed public support for the Games, lacked name recognition and had no real experience hosting major international sporting events.

Still, Almaty narrowly lost by a vote of 44-40. That left Beijing, which hosted the 2008 Summer Games but which does not have much of a winter sports history. It will use some existing arenas from 2008, including the Bird’s Nest stadium. But upon winning the 2022 bid, Beijing officials said they would also rely on an extensive artificial snow-making operation and a high-speed train project that would link Beijing with clusters of venues in the mountains as far as 100 miles away.

Bidding for the 2026 Games experienced a similarly withered field of candidates as public interest flagged or rose in opposition in Calgary, Alberta; Sion, Switzerland; Graz, Austria; and Sapporo, Japan. The I.O.C. did not consider a bid by Erzurum, Turkey, to be sustainable.

The I.O.C. separated the Winter Games from the Summer Games, beginning in 1994, in order to give the Winter Olympics more prominence. They have moved from historical settings in ski resorts to larger cities like Turin, Vancouver and Salt Lake City (which could be a favorite to host the 2030 Games).

Inevitably, costs rose, and on some occasions there has been little hint of winter. In Sochi, the climate is so temperate that palm trees flourish there; at times, it got so warm during the 2014 Winter Games that some sun bathers jumped into the Black Sea in their Speedos.

Also, while the Summer Olympics feel like an international sporting event, the Winter Games can feel empty, lacking in spectators and the spirit of a global happening. Instead, they sometimes more closely resemble a set for a reality television series.

So far, the I.O.C. has failed in its effort, inaugurated in 2014, to attract more candidates to host the Winter Games with more inviting bid rules. And now it is urgently counting on northern Italy to help reverse that lack of interest.

Jubilant crowds welcomed the televised verdict in a central Milan square, where hundreds of people gathered to watch a live stream on a large screen. In Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Dolomite Alps, residents sang the national anthem.

Gaia Pianigiani contributed reporting from Siena, Italy